T1 ToneMatch® Audio Engine / Digital Delay for Second L1®

Here are some notes on how to use your T1 ToneMatch Audio Engine or T4S/T8S ToneMatch® Mixers to drive a main L1® or L1 Pro at the front of the house and a second L1® or L1 Pro farther back. The goal is to provide sound in a long room, in this case approximately 50 feet wide by 250 feet long. The room may be three quarters full or we may need only provide coverage out to about 200 feet. |

Terms

- Main L1® is the one at the front of the house centered on the 50 foot wall.

- Secondary L1® is the one farther back, approximately 100-125 feet down the long wall.

Connections and Settings

T1® Inputs

- 1 Microphone

- 2 Microphone / Instrument or Mixer

- 3 Used for Digital Delay processing

- 4/5 USB input from Computer

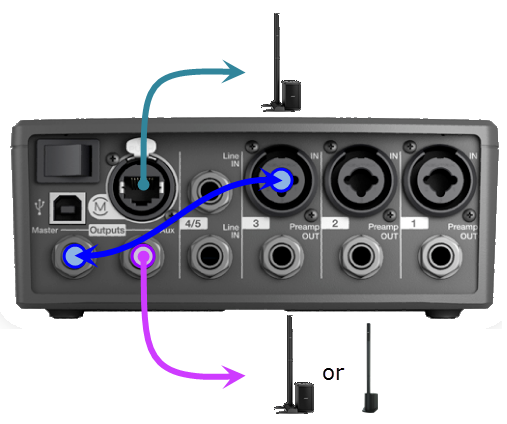

T1® Outputs

- T1 ToneMatch® Audio Engine (Ethercon Connection) goes to the Main L1®.

- Main ¼ inch output goes to Channel 3 input.

- Aux ¼ inch output goes to Secondary L1® Analog Input

Ordinary connections

Connect inputs for Channels 1, 2 and 4/5 in any way you like. Ensure that the setting for Aux is Mute for all.

Channel 3 - Used as Delay Channel - Settings

We are using Channel 3 to process to create a delayed version of the Main output, and direct it to the Aux output and from there to the Secondary L1®

Turn level down, Ch 3 Mute

We are setting the Level to zero and we will not change this while using Channel 3 for Digital Delay processing. We are setting the Mute as an additional precaution.

Settings for Channel 3

- Turn on Channel 3 CH Edit

- Turn the main Selector to Digital Delay

Digital Delay – Mix and Time

Set the Mix to 100%. This way we are outputting the delayed signal only.

We are setting the Time to 100ms to start. We will fine tune the time setting by ear later.

Digital Delay – Fdbk (feedback)

- Press the third button to switch from Time to Fdbck.

- Rotate the button to set the Fdbk to 0%. We only want to hear the delayed signal once.

Channel 3 Aux

- While still working with the CH 3 Edit lit turn the main selector to Aux.

- Set the Level to 100% so we send the full signal to the Aux output.

Aux – Tap Setting

- Press the Tap (middle) button, then turn set it to Pre: With EQ & FX then press it to select your choice.

Main Out (¼ inch) to Channel 3 Input

Run a short 1/4 inch patch cord from the analog Main Out to Channel 3 input.

The final outcome looks like this.

And then you would connect your inputs.

Summary

The result of all these settings is the analog Main output is flowing through to Channel 3. Channel 3 is delayed 100ms once. The delayed signal is routed to Aux. The original signal is discarded, but that's okay because the original sources are still flowing through to the Main output through the T1 ToneMatch® Audio Engine port.

Positioning the Secondary L1®

You are going to have to position the Secondary L1® based on the room layout, sight lines, access requirements and what you hear when you set it up. In this particular case, try for about half-way between the Main L1® and the back of the area you are required to fill. If you can put it in the middle of the 50 foot width of the room and aim it toward the back, that would be good.

If you cannot hit the 'ideal' we can still compensate by setting the Delay Time (see next section).

Fine Tuning the Delay Time

Tech Note: Distance in feet x .91 milliseconds = delay in milliseconds

Working on the assumption that the second LL1® is approximately 110 feet, the delay would be 100 milliseconds. We just used 100 as a preliminary setting.

Put the second L1® approximately halfway down the area to be covered by your two L1®s. Aim it away from the main L1®. We want to avoid overlapping the sound fields of the the two L1®s.

Turn up the T1 ToneMatch® Audio Engine Master level and you should hear your inputs through the Main L1®. Turn up the Secondary L1® Analog Input until you can hear both L1®s.

Have someone stand close to the second L1®. This is your 'listener'.

Use a child's "clicker" or something that produces a sharp, short clicking sound to send a "click" through a microphone into the T1 ToneMatch® Audio Engine. MikeZ-at-Bose suggested a metronome for this source.

Edit Channel 3, Digital Delay Time setting. Adjust the time until the listener hears only one click instead of two. The means that you have synchronized the sound from both L1®s for people who are in the overlap area of the two sound fields.

Supporting Notes

Here is an excerpt of an article called the Digital Delay Advantage

How to Synchronize Your Signals

In the 1930s, engineers synchronized the low and high frequency speakers in movie theaters by feeding a sharp click through the system. They moved the speakers until they could only hear a single sharp click coming from both speakers. You can use this same method with a common child’s toy called a clicker.

Pressing the thin metal strip makes a loud sharp click. A clicker is especially useful when synchronizing the direct sound from the performer with the sound from the loudspeakers.

Source: The Digital Delay advantage Alternate link http://www.manualslib.com/manual/403058/Sabine-The-Digital-Delay-Advantage.html

More excerpts from the Sabine article (no longer available online).

- Why Digital Delays?

The most intelligible sound occurs when two people speak face to face. The sound is loud and dry and the direction of the sound aligns with the speaker. It stands to reason that the most intelligible sound systems are the ones that come closest to emulating face to face communication. If this is your goal, a digital delay is essential to your sound system.

Until recently, a digital delay's cost was prohibitive for the average user. Only high-end applications could

justify the cost. But recent drops in component prices now put the benefits of digital delays within

affordable reach of every user.

There are three distinct applications for digital delays. The first and most important is synchronization

of the loudspeakers to control excess reverberation and echo. Secondly, digital delays help control

comb filter distortion, and finally, digital delays are useful for aligning the acoustic image so the

direction of the sound seems to come from the performer rather than the loudspeaker.

This guide goes beyond the typical operating manual that explains only the front and back panel

adjustments. Instead, we discuss the basic acoustical concepts needed to get the most out of your digital

delay and present examples of several practical applications.

- Loudspeaker Synchronization

Sound travels at about 1,130 feet per second in air, or about 1 millisecond per foot. On the other hand, electronic signals travel almost one million times faster through your sound system to the loudspeakers — effectively instantaneous. The main task of digital delays is to synchronize multiple loudspeakers so the sound traveling different distances through air arrives at the listener's ears at about the same time. Synchronizing the loudspeakers reduces reverberation and echoes for improved intelligibility.

- How to Synchronize Your Signals

There are several powerful tools available for precisely measuring the time a loudspeaker signal takes to arrive at a certain point in the audience. Most of these tools are very sophisticated and tend to be quite expensive. Fortunately, simpler tools are sufficient for most applications. In the 1930s, engineers synchronized the low and high frequency speakers in movie theaters by feeding a sharp click through the system. They moved the speakers until they could only hear a single sharp click coming from both speakers. You can use this same method with a common child's toy called a clicker. Pressing the thin metal strip makes a loud sharp click. A clicker is especially useful when synchronizing the direct sound from the performer with the sound from the loudspeakers.

Alternatively, you can use a phase checker especially for synchronizing the signals of two loudspeakers

(either LF and HF or two full range systems), since most of the phase checkers include a click generator

and receiver. Phase checkers are quite affordable and have other uses besides synchronization.

- Processing (or Group) Delays

Converting signals back and forth from the analog to digital domain will slightly delay the signal. These conversion delays are often called processing (or group) delays, and usually range between 0.9 to 5 milliseconds. You will notice that Sabine delays display the processing delay as the smallest possible delay value. You can simply bypass the unit for 0 seconds delay. Not all manufacturers acknowledge processing delays in their specifications, but you must take them into account when synchronizing your system. Make sure all digital equipment is on and not bypassed when synchronizing. Also, be careful to make an appropriate adjustment in your delay lines if you later add any type of digital equipment to the system.

- Center Cluster Speakers

Center cluster speakers offer several advantages over systems that have speakers mounted on the sides. The most obvious advantage is that the distance to the closest and most distant locations in the audience is almost equal, so most listeners hear similar levels of amplified sound. Center clusters also offer two other advantages regarding the visual imaging.

Studies have shown that people can detect even small horizontal changes in the direction of a sound source, but vertical shifts are much less noticeable. This suggests that the sound from center-cluster speakers is more likely to be visually aligned with the performer than loudspeakers placed on each side of the stage.