Difference between revisions of "File:Tone-Graph.jpg"

(http://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/features/woods/Tone/) |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

http://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/features/woods/Tone/ | http://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/features/woods/Tone/ | ||

| + | |||

| + | t<table><tr> | ||

| + | <td valign="top"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The Tone Zone: Tonewoods and their Relative Frequency Ranges== | ||

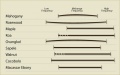

| + | One of the most common ways to describe a wood’s tonal properties is in terms of its frequency range, which is often broken down into low-end frequencies, midrange and high-end frequencies. Picture it as a visual spectrum, as we’ve done in the chart above, with the lower frequencies on the left and the higher frequencies on the right. The graph line for each wood visually depicts its general tonal range. Rosewood and ovangkol, for example, tend to resonate with more low-end frequencies, whereas koa, cocobolo and maple tend to sound brighter from having more top-end frequencies. Note also rosewood’s “scooped” midrange and ovangkol’s fuller midrange. The dotted lines for walnut and koa denote the expansion of low-end frequency range as the guitar opens up after a period of playing it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === “Bone Tone” and Other Tone-Shaping Variables=== | ||

| + | For all our talk about the sonic shadings of tonewoods, a guitar’s tonal colors reside largely in a player’s hands. If acoustic tone is an equation of sorts, it might read something like: body shape + tonewoods + string type + player = tone. Here are a few points to ponder about balancing that equation to get the tone you want. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===String Type=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the easiest things you can do to alter the sound of a guitar is change your type of strings. With steel-string acoustics, whether you use a coated string like Elixir (which we use at the Taylor factory), an 80/20 bronze, or a phosphor/bronze can affect the volume, brightness and warmth of your tone. “If you want to invest $60-70 in a great education,” says Taylor VP of Marketing Brian Swerdfeger, “try buying four or five different types of strings. You’ll want to record the guitar with each set since we tend to have poor audio memory, but it could be something simple, even your phone answering machine, as long as it’s the same device. You might be surprised to learn that you thought you liked a certain type of strings, but after listening back realize you like a different set more.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===String Gauge=== | ||

| + | String gauge tends to be optimized for the body size of a guitar, with heavier gauge strings typically used on bigger guitars. If you’re putting light gauge strings on a bigger guitar, for example, you’re not going to get as much dynamic range; you’ll sacrifice some tone and volume. “If you’re chasing a certain sound, like an old school roots-rock, heavy-strum, low-fi thing,” Brian says, “light-gauge strings won’t deliver that.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Also keep in mind that although the string gauges we factory-install here at Taylor are optimized for a range of use, there’s room to adjust to suit your playing approach. We put light gauge strings on our Grand Concert and Grand Auditorium models, but you can use mediums (although we don’t recommend it for models with cedar tops). Similarly, we use mediums on a GS and Dreadnought, but you could try lights. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===“Bone Tone”=== | ||

| + | Beyond guitar materials and playing tools, what the player is physically doing to the strings is a huge source of a guitar’s sound. Brian likes to refer to one’s personal technique as “bone tone.” It’s the way we hold a guitar, attack and fret the strings — the overall physics we bring to the guitar. A player’s bone tone might be described in terms of brightness and darkness. It helps to consider how one’s bone tone might match up with the relative brightness or darkness of the shape and woods one chooses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Bright players have lots of attack,” Brian explains. “As a result, you don’t hear the midrange bloom as much. A lot of times they’ll complain about a quick decay, that their tone doesn’t have fullness. What can that person do? They can play darker tonewoods. They can try playing more with the pads of their fingers versus nails. I also tell people to beware of the death grip with the fretting hand. Some people squeeze so hard that they pull notes sharp. A bright player who presses really hard into the fretboard is making a bright connection there in addition to his or her attack.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fingerstyle players with darker hands, Brian says, can use a little more nail strike in their attack. | ||

| + | Dark players also can play brighter tonewoods more successfully. “A bright player on a bright guitar like koa or maple might sound thin or wimpy, but a dark player will sound fuller,” he says. “So, | ||

| + | by selecting tonewoods, you can take a guy who has really bright, plinky hands, give him a warm-sounding guitar, and he’ll tend to sound really good.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Brian has also observed that with more experienced players, controlling bone tone is less about the dexterity of one’s fretting hand and more about what one can do with one’s picking/strumming hand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The hallmark of a seasoned player is someone who can control their dynamic levels from hard to soft, and create different degrees of brightness or darkness by the way they strike strings,” he says. “I can always tell mature players by what they do with their picking hands.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Pick Materials=== | ||

| + | These include the pads of one’s fingers, natural fingernails, acrylics, fingerpicks and flatpicks. Pick materials can make a significant difference, whether it’s plastic, tortex or something else, as can the thickness of the pick and the edge that you use (pointy versus the more rounded end). “I tell people to go out and spend $5 on a variety of picks,” Brian says. “People may find that they each have a different tone or that they prefer a different material or thickness.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | <td valign="top"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Talking Tone == | ||

| + | ===Acoustic guitar terms at a glance=== | ||

| + | Like wine connoisseurs, foodies and other sense-driven aficionados, we guitar lovers wield colorful lingo to describe our subjective indulgences. The good news: Guitar talk actually translates into definable qualities of sound. The bad news: Our ears, like our taste buds or senses of smell, are wired in a multitude of different ways, so we don’t always hear tone consistently. Nonetheless, getting a handle on a few basic terms will help you sharpen your ear to the nuances of tone. Below is our take on an earful of commonly used expressions relating to tone. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Fundamental=== | ||

| + | The true frequency, or pitch, of a note. A low E, for example vibrates at a frequency of 82.407 hertz (Hz). (1 Hz = 1 vibration per second.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Overtones=== | ||

| + | Multiples of a fundamental frequency, also referred to as harmonics, which occur as a string vibrates, creates wave patterns, and the harmonics stack up. The term “bloom” is used to describe the sonic effect of the overtones as they stack up over the decay of the note. Although overtones tend to be more subtle than the fundamental, they add richness to a sound. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Midrange=== | ||

| + | On car stereo or home audio systems, the frequency response often ranges between 20 Hz to 20 kilohertz (kHz). Midrange covers from 110 Hz, which is a low A string, up as high as 3 kHz. High frequency (treble) tones tend to reside beyond that. If one considers where an acoustic guitar’s pitch range falls, predominantly all the notes on the fretboard occupy the midrange of the frequency spectrum that can be heard. It’s where voice is; it’s the middle part of a piano. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Scooped=== | ||

| + | Attenuated, or slightly diminished. Picture the visual connotation, like on a graphic equalizer. If you scoop the midrange, you dip those middle sliders down a bit, which would look like a smiley-face curve. The result would be a level low end and high end, but a little less of the midrange. (See rosewood midrange graph on page 22.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Bright=== | ||

| + | Treble emphasized, or with a lower degree of bass. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Dark=== | ||

| + | Bass tones emphasized or tone with a lower degree of treble. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Warm=== | ||

| + | Softer high frequencies, like if you took a little of the very top off the treble. A rosewood GA has a warm treble sound; the treble is there but it’s not overly bright like a maple GA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Sparkle=== | ||

| + | In a general sense, the opposite of warm; some excited high frequencies. Koa or maple tends to have a high-end sparkle. Same idea as “zing.” Sparkling treble frequencies might also be described as “zesty.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Meaty=== | ||

| + | Lots of midrange, with a full low end. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Crisp=== | ||

| + | Similar to warm, but with a little more treble. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Presence=== | ||

| + | Generally, the treble frequencies that provide articulation and definition. If you put your hand over your mouth and talk, you have less presence. One can still hear and understand the words, but they will have less presence because they lack the articulation of a clearly defined high frequency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Ceiling=== | ||

| + | A defined boundary, often used in reference to volume (see Adirondack spruce). A guitar or wood’s ceiling is the point at which it stops delivering volume or tone. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Decay=== | ||

| + | The way a note that’s left to ring out diminishes over time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | </tr></table> | ||

Revision as of 14:54, 15 September 2009

http://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/features/woods/Tone/

t

The Tone Zone: Tonewoods and their Relative Frequency RangesOne of the most common ways to describe a wood’s tonal properties is in terms of its frequency range, which is often broken down into low-end frequencies, midrange and high-end frequencies. Picture it as a visual spectrum, as we’ve done in the chart above, with the lower frequencies on the left and the higher frequencies on the right. The graph line for each wood visually depicts its general tonal range. Rosewood and ovangkol, for example, tend to resonate with more low-end frequencies, whereas koa, cocobolo and maple tend to sound brighter from having more top-end frequencies. Note also rosewood’s “scooped” midrange and ovangkol’s fuller midrange. The dotted lines for walnut and koa denote the expansion of low-end frequency range as the guitar opens up after a period of playing it.

“Bone Tone” and Other Tone-Shaping VariablesFor all our talk about the sonic shadings of tonewoods, a guitar’s tonal colors reside largely in a player’s hands. If acoustic tone is an equation of sorts, it might read something like: body shape + tonewoods + string type + player = tone. Here are a few points to ponder about balancing that equation to get the tone you want. String TypeOne of the easiest things you can do to alter the sound of a guitar is change your type of strings. With steel-string acoustics, whether you use a coated string like Elixir (which we use at the Taylor factory), an 80/20 bronze, or a phosphor/bronze can affect the volume, brightness and warmth of your tone. “If you want to invest $60-70 in a great education,” says Taylor VP of Marketing Brian Swerdfeger, “try buying four or five different types of strings. You’ll want to record the guitar with each set since we tend to have poor audio memory, but it could be something simple, even your phone answering machine, as long as it’s the same device. You might be surprised to learn that you thought you liked a certain type of strings, but after listening back realize you like a different set more.” String GaugeString gauge tends to be optimized for the body size of a guitar, with heavier gauge strings typically used on bigger guitars. If you’re putting light gauge strings on a bigger guitar, for example, you’re not going to get as much dynamic range; you’ll sacrifice some tone and volume. “If you’re chasing a certain sound, like an old school roots-rock, heavy-strum, low-fi thing,” Brian says, “light-gauge strings won’t deliver that.” Also keep in mind that although the string gauges we factory-install here at Taylor are optimized for a range of use, there’s room to adjust to suit your playing approach. We put light gauge strings on our Grand Concert and Grand Auditorium models, but you can use mediums (although we don’t recommend it for models with cedar tops). Similarly, we use mediums on a GS and Dreadnought, but you could try lights. “Bone Tone”Beyond guitar materials and playing tools, what the player is physically doing to the strings is a huge source of a guitar’s sound. Brian likes to refer to one’s personal technique as “bone tone.” It’s the way we hold a guitar, attack and fret the strings — the overall physics we bring to the guitar. A player’s bone tone might be described in terms of brightness and darkness. It helps to consider how one’s bone tone might match up with the relative brightness or darkness of the shape and woods one chooses. “Bright players have lots of attack,” Brian explains. “As a result, you don’t hear the midrange bloom as much. A lot of times they’ll complain about a quick decay, that their tone doesn’t have fullness. What can that person do? They can play darker tonewoods. They can try playing more with the pads of their fingers versus nails. I also tell people to beware of the death grip with the fretting hand. Some people squeeze so hard that they pull notes sharp. A bright player who presses really hard into the fretboard is making a bright connection there in addition to his or her attack.” Fingerstyle players with darker hands, Brian says, can use a little more nail strike in their attack. Dark players also can play brighter tonewoods more successfully. “A bright player on a bright guitar like koa or maple might sound thin or wimpy, but a dark player will sound fuller,” he says. “So, by selecting tonewoods, you can take a guy who has really bright, plinky hands, give him a warm-sounding guitar, and he’ll tend to sound really good.” Brian has also observed that with more experienced players, controlling bone tone is less about the dexterity of one’s fretting hand and more about what one can do with one’s picking/strumming hand. “The hallmark of a seasoned player is someone who can control their dynamic levels from hard to soft, and create different degrees of brightness or darkness by the way they strike strings,” he says. “I can always tell mature players by what they do with their picking hands.” Pick MaterialsThese include the pads of one’s fingers, natural fingernails, acrylics, fingerpicks and flatpicks. Pick materials can make a significant difference, whether it’s plastic, tortex or something else, as can the thickness of the pick and the edge that you use (pointy versus the more rounded end). “I tell people to go out and spend $5 on a variety of picks,” Brian says. “People may find that they each have a different tone or that they prefer a different material or thickness.”

|

Talking ToneAcoustic guitar terms at a glanceLike wine connoisseurs, foodies and other sense-driven aficionados, we guitar lovers wield colorful lingo to describe our subjective indulgences. The good news: Guitar talk actually translates into definable qualities of sound. The bad news: Our ears, like our taste buds or senses of smell, are wired in a multitude of different ways, so we don’t always hear tone consistently. Nonetheless, getting a handle on a few basic terms will help you sharpen your ear to the nuances of tone. Below is our take on an earful of commonly used expressions relating to tone. FundamentalThe true frequency, or pitch, of a note. A low E, for example vibrates at a frequency of 82.407 hertz (Hz). (1 Hz = 1 vibration per second.) OvertonesMultiples of a fundamental frequency, also referred to as harmonics, which occur as a string vibrates, creates wave patterns, and the harmonics stack up. The term “bloom” is used to describe the sonic effect of the overtones as they stack up over the decay of the note. Although overtones tend to be more subtle than the fundamental, they add richness to a sound. MidrangeOn car stereo or home audio systems, the frequency response often ranges between 20 Hz to 20 kilohertz (kHz). Midrange covers from 110 Hz, which is a low A string, up as high as 3 kHz. High frequency (treble) tones tend to reside beyond that. If one considers where an acoustic guitar’s pitch range falls, predominantly all the notes on the fretboard occupy the midrange of the frequency spectrum that can be heard. It’s where voice is; it’s the middle part of a piano. ScoopedAttenuated, or slightly diminished. Picture the visual connotation, like on a graphic equalizer. If you scoop the midrange, you dip those middle sliders down a bit, which would look like a smiley-face curve. The result would be a level low end and high end, but a little less of the midrange. (See rosewood midrange graph on page 22.) BrightTreble emphasized, or with a lower degree of bass. DarkBass tones emphasized or tone with a lower degree of treble. WarmSofter high frequencies, like if you took a little of the very top off the treble. A rosewood GA has a warm treble sound; the treble is there but it’s not overly bright like a maple GA. SparkleIn a general sense, the opposite of warm; some excited high frequencies. Koa or maple tends to have a high-end sparkle. Same idea as “zing.” Sparkling treble frequencies might also be described as “zesty.” MeatyLots of midrange, with a full low end. CrispSimilar to warm, but with a little more treble. PresenceGenerally, the treble frequencies that provide articulation and definition. If you put your hand over your mouth and talk, you have less presence. One can still hear and understand the words, but they will have less presence because they lack the articulation of a clearly defined high frequency. CeilingA defined boundary, often used in reference to volume (see Adirondack spruce). A guitar or wood’s ceiling is the point at which it stops delivering volume or tone. DecayThe way a note that’s left to ring out diminishes over time.

|

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 14:44, 15 September 2009 |  | 567 × 353 (50 KB) | ST (talk | contribs) | http://www.taylorguitars.com/guitars/features/woods/Tone/ |

- You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following page links to this file: