5th Anniversary of L1® Launch

Contents

To Musicians Everywhere,

It was five years ago, on October 15, 2003, that we introduced an entirely new approach to live music amplification.

At the time we launched, I can honestly say that while we were utterly confident through our testing that the benefits we were claiming were real, we just didn't know if musicians would want to try it, much less spend their hard-earned money for it. I literally lay awake many a night in the days, weeks and months leading up to our first press event on October 15 wondering if anyone was going to buy even a single L1 system.

Oh. What a great ride it has been.

Not only was my anxiety unfounded, what's happened has surpassed even what we allowed ourselves to dream when we were alone and thinking about how profound and positive the changes were we were observing in our live music tests.

In the past five years many tens of thousands of musicians in over one hundred countries have purchased one or more L1 systems. And what they have said about the differences owning an L1 has meant to them now constitutes an avalanche of positive evidence -- much of it here on this online forum.

The L1 approach is what I would call radical. Fundamentally, it replaces most or all of the amplification equipment that evolved in the last half of the 20th century. It replaces triple systems (PA, monitors, backline) which were found in our research to be at the heart of the persistent and acute complaints from musicians and audiences alike about the sound of live amplified music, with a simple, naturalistic approach that is more based on the evolution of unamplified music than the ever-louder, ever more complicated, ever more isolating amplification systems that evolved in the last 50 years.

In the history of hi-fi, as a parallel industry, I can think of no technology that is as radical. That is why we felt it was possible to call the L1 approach an [i]entirely[/i] new approach.

The fact that musicians around the world, including most of you, were willing to cast off years of refinement in triple systems -- and more pointedly, attempt to cast of the problems that never went away no matter how much more sophisticated the gear became -- is for me an extraordinary story of courage and daring.

The fact that you did this, and that the results as written here and elsewhere, and on the delighted expressions of audience members, is something that I will treasure forever. It is something that I literally think about every day of my life, and [i]will[/i] think of every day for the rest of my life.

Thank you, from the bottom of my heart.

We'd like to take the opportunity afforded by our 5th anniversary to share with you some of the things that occurred in the ten or so years of work that preceded the launch, and also some of the things that happened as we launched, and as this community started to build.

Many of my colleagues will contribute their part of the story.

We also invite you to share any of your experiences that you feel could contribute to recounting and recapturing some of the early history of the L1.

It is hard to believe that such a radical new technology has done so well. When I scan for similar successes of something so radical succeeding so much in such a short time, I come up with little. The Fender bass comes best to mind. Just imagine what it will be like to write the 10-year story of the L1.

With love, admiration and appreciation for musicians everywhere,

Ken Jacob Co-originator of the L1 research project

Bose in Live Music Before the L1® System

When Bose introduced the L1 system in October of 2003, we had to introduce ourselves as a company to musicians.

Actually, some of you already knew us.

The Bose 800, our first professional loudspeaker, introduced in the early 1970s was very popular, and was used by many musicians, as PA, occasionally built into backline amps, and as a monitor.

Here's a photo of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band using 800s on stage as monitors. The exact date of this performance is unknown. Perhaps one of you can pinpoint it to at least a tour?

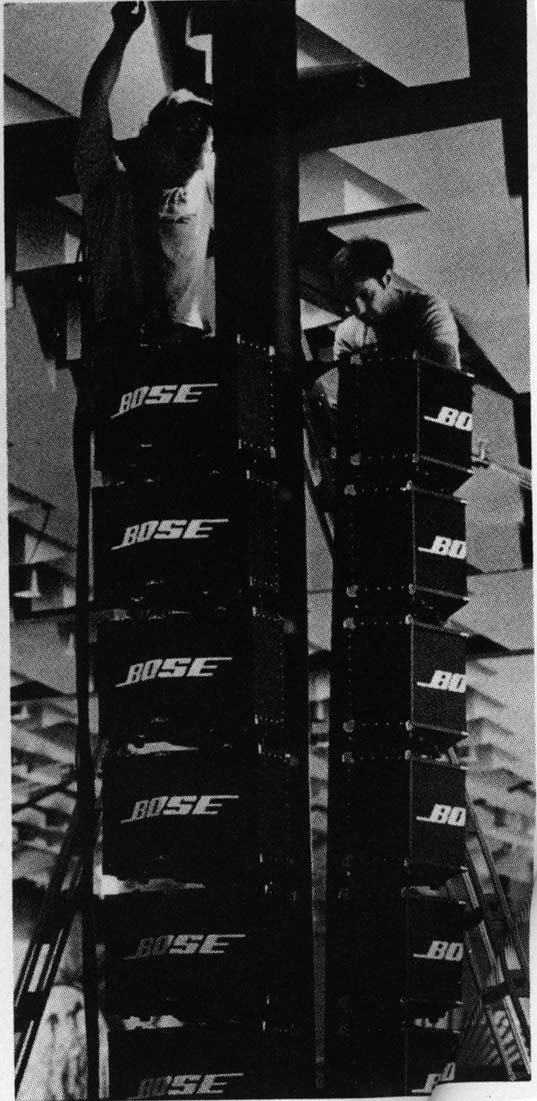

We also did a large scale project in the 1970s at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Montreux, Switzerland using large vertical stacks of Bose 800s.

Here's a photo of the stacks.

You can see how they blended in to the environment.

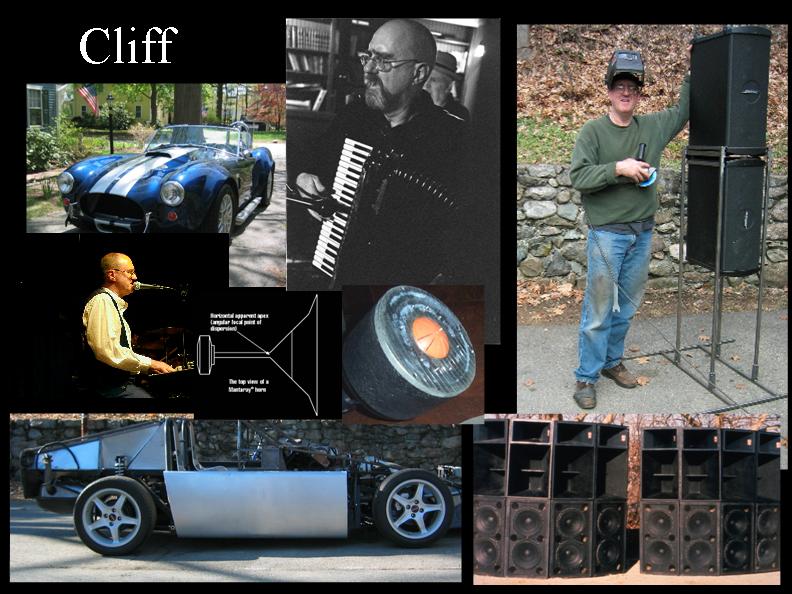

Cliff Henricksen; L1® Inventor

<section begin="Cliff Henricksen L1® Inventor"> Cliff Henricksen came to Bose in November of 1993.

He had worked for the giants in the professional sound industry and had a number of fundamental patents in his name.

You can see the tangerine phase plug for high-SPL compression drivers, and the Manta-Ray horn.

It is highly likely that there are more loudspeakers installed around the world in larger venues containing devices that use one or more Henricksen patents than any other inventor.

Cliff came to us from a very small, exciting company called US Sound, in 1993. He can tell you more about our work together at the Albertville Olympics. We were just knocked out by his patented loudspeaker technology.

Cliff joined the acoustic research group after the purchase was completed, where I was working.

That car is almost finished (the silver one). That's basically the frame and aluminum inner-structure. It's painted now. Got me a Ford V8 in'ere, bwawh.

<section end="Cliff Henricksen L1® Inventor">

Earliest Activities

Hi everybody

Ken Jacob and I basically created the L1 together. It's a long story.

I came to work at Bose by selling my company, US Sound, to Bose in 1993. It all had to do with high-output fire-breathing speakers used in rock&roll-level systems for professional sports in arenas and stadiums. The designs still exist at Bose and are called "Panaray LT".

My partners went their separate ways and I became a Senior Engineer in the Acoustics Research division of Bose. They gave me a beautiful office with a panoramic view of lovely New England forests and lakes. Ken was in charge of the department at the time and, interestingly, a lot of great people I still work with were in the same department.

So, literally, my very first day of work in Framingham, I had a sort-of organizational meeting with Ken. Ken had a lot of experience, in college and afterwards, as a "sound man" in theater and for bands. As a result, he was all over the horror of how music was amplified, what with monitors, instrument amps and PA cluttering even the smallest stages and amplifiers exceeding 1KW easily available. Plus mixers, cables, everything. It took forever to set this stuff up, a van to move it and hours to get a highly-compromised sound for everyone to play to. It was way too loud onstage and definitely in the audience, not that musicians would know this. I can remember audiences cringing from sound levels and feeling helpless to do anything about it, sort of like we all got on this awful rollercoaster and the whole thing was careening in chaos, at ridiculous speeds that it was never intended for. Not a real pleasant memory, but one that doesn’t need to be re-experienced. And so, I sure agreed with Ken, knowing full well what a pain it is to play out with a band and suspecting why live music was in such a bad state of health (customers driven away by poor quality and too much quantity of it).

"Why is this?" was Ken’s question in our first meeting. My reply was "hm, let me think about this". So we agreed to meet once a week and talk about this, with me doing some digging and thinking and concluding and reporting. Before too long, we began to realize the extent of the profound chasm that had been inadvertently created between the audiences and the musical artists. There was way way too much gear on most stages and we easily saw three totally separate and totally conflicting systems being used by most bands; the “triple amplification system”. This all came out of its effective use in big concerts. Unfortunately, musicians everywhere, even in little wedding bands, started using it, just like their musical heroes playing in hockey arenas. It was like using an atomic bomb to get rid of ground-hogs in your garden. Yeah, it works, but it kills everything around. Not only that, but musicians had, again inadvertently, lost their engagement with their audiences. They couldn’t tell what the audiences were getting from their artistic efforts and they couldn’t do much about it. Someone else had their hands on the controls.

My suggestions for a possible technological solution to this epidemic in music-land came from recent industry vibrations about the special qualities of line arrays and from the brave experiments by the Grateful Dead, putting the whole sound system, made up partially by bass and guitar line arrays and a large central vocal system. The latter made so much sense; putting the system behind the band so they could hear it. The Dead used a canceling microphone system too, to reduce feedback in large-audience shows. Ken and I knew it was imperfect, but the idea of a system the band could use and hear and control was the inspiration. My suggestion was using line arrays that were very small in width and above head-level in height. This would give very wide horizontal acoustical radiation and an array-high vertical pattern. It would also give a very gradual change in level with distance from the array. I decided that one system per player would probably work, although at first I thought that horizontal waveguides would be necessary to direct the sound, and so would control by an audience-situated mix engineer. Boy, was that ever wrong on both counts. I wrote an early document to Ken in September of 1995 during our ongoing search for something that would work for most players.

You can view it Historic Document Showing L1® Invention for First Time

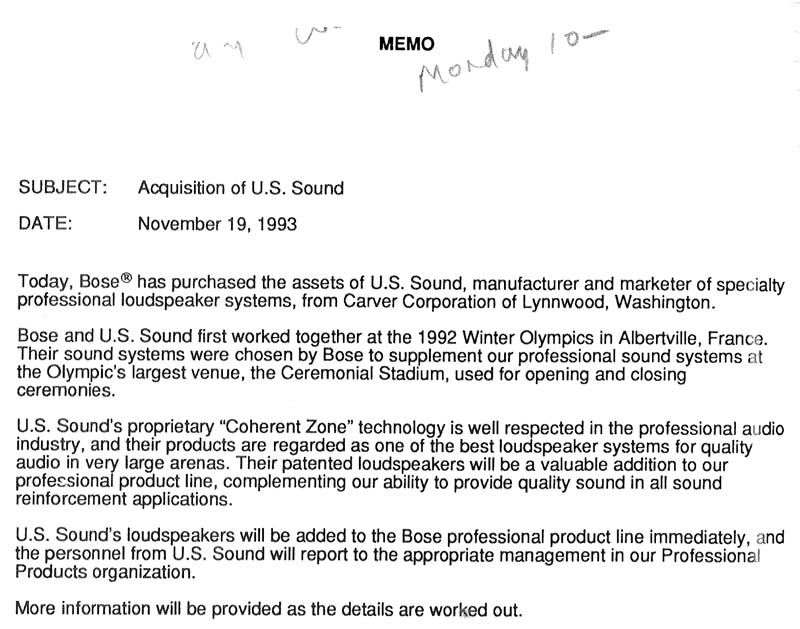

Cliff joined us in November of 1993 and so this first meeting about live music occurred soon thereafter.

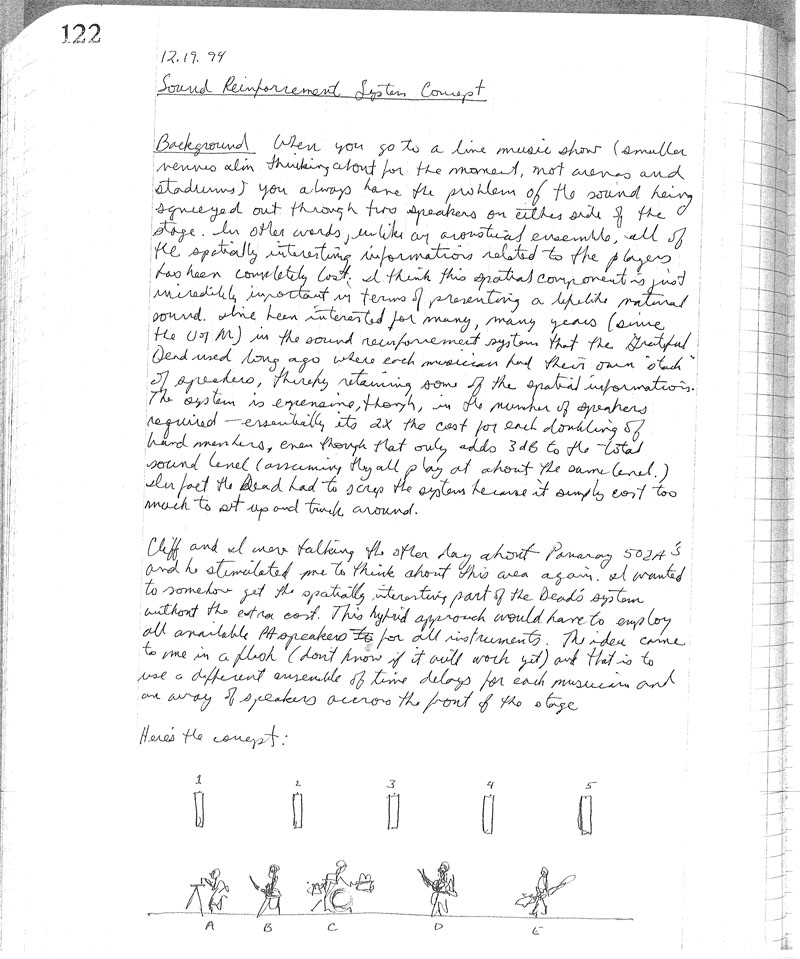

Yesterday, I was going through my engineering notebooks from that time period, and I found the first entry that mentions Cliff.

I found it interesting.

This must have been just before the deal was done, because the entry is also from November of 1993.

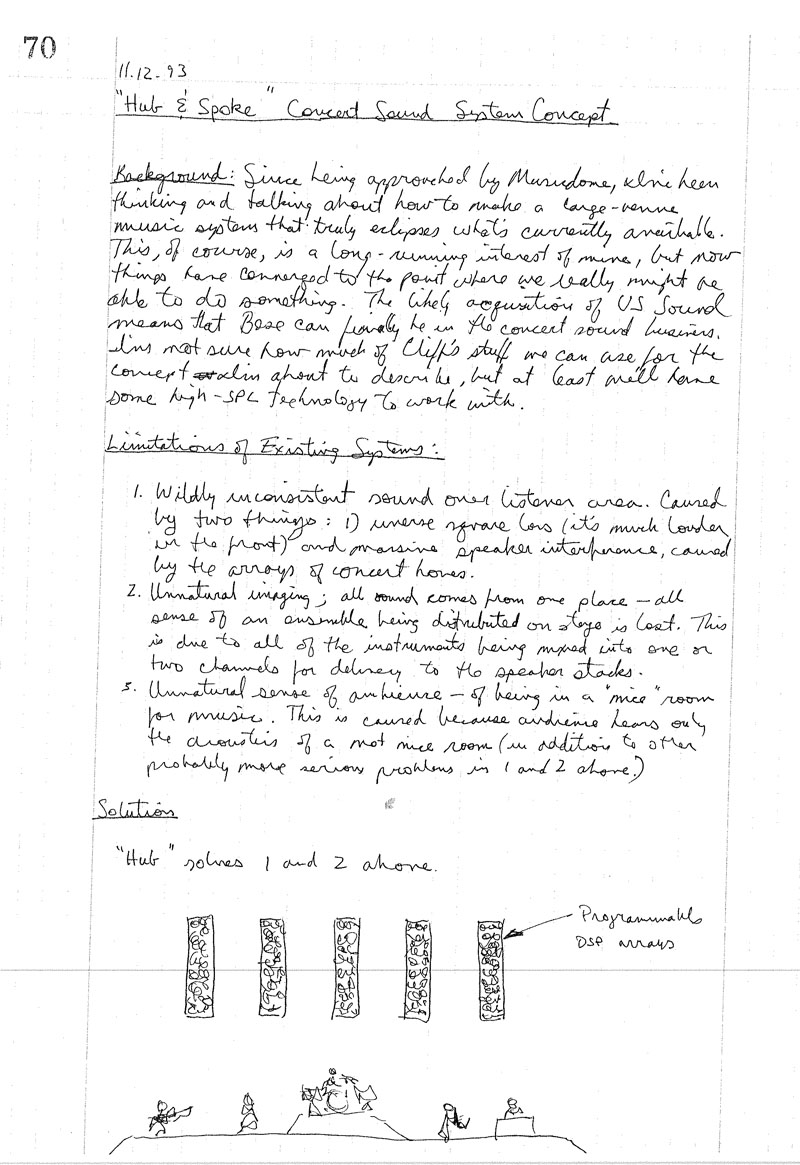

What's really interesting to me is the idea that we were already thinking about a system that would preserve the natural spatial presentation of unamplified performances.

You can also see how inspired I was by the Dead's Wall of Sound because it partly did this (the vocals were all summed to a central cluster, something I wanted to avoid.)

Also yesterday I found another notebook entry, just a few weeks later.

Here, it's even more clear that Cliff and I are working on "the problem" together. I believe this is clearly after the "first meeting" that Cliff has always recalled so vividly.

This is the earliest document we have found that shows a system for musicians playing in the smaller to medium sized venues that dominate musical performances around the world.

I got goosebumps when I found this.

Cliff also found some documents when he was moving his office a few weeks ago, documents that were lost.

I love "...squeezed out of two speakers on either side of the stage". And that's what it is.