Feedback / Microphone

What is feedback and how does it occur?

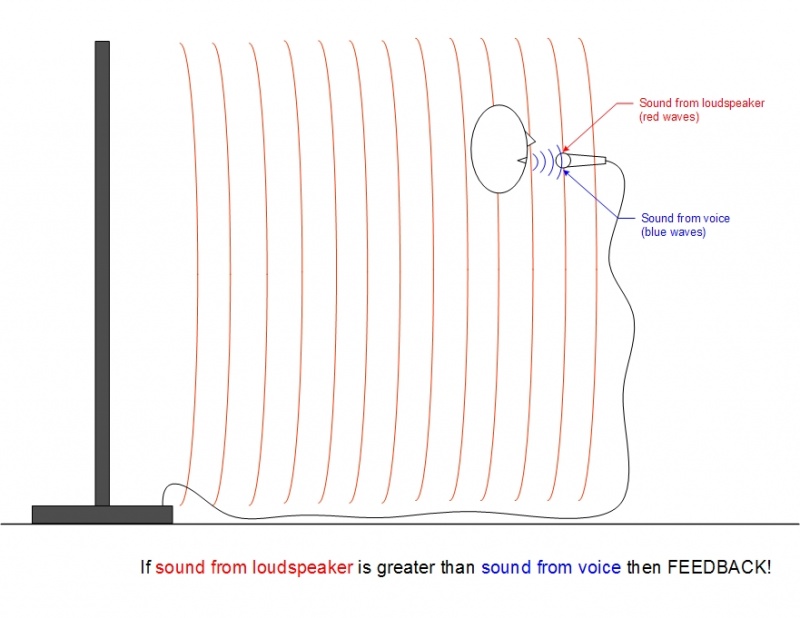

Feedback occurs when the sound from the loudspeaker (or loudspeakers if a microphone is connected to more than one) is louder at the microphone than the sound of the voice.

This fundamental fact is shown in the figure below.

Techniques For Reducing Feedback

Gain Staging

If you are having issues with feedback, check your gain staging. This is critical to getting sufficient gain before feedback in live performance applications.

Take two minutes to watch this video by clicking on the picture below. Gain setup for a vocal microphone

- If you are using an L1 Classic or L1 Model I follow the instructions exactly as shown in the video.

- If you are using the T1 ToneMatch Audio Engine, the principles are the same as shown on the video: simply substitute the trim on the T1® for the trim on the Classic or Model I.

Close Microphone Technique

Get close to the microphone when you want to be loud. No other technique has a big an impact on feedback. Each halving of distance is approximately another 6 dB of gain before feedback. This relationship in physics is known as the Inverse Square Law. This means that the difference between working a microphone at 2 inches, and 1/4 inch is 18 dB, which is more than twice as loud. While good mic technique often involves "working" the microphone at different distances, singers must be mindful of the fact that small changes in distance from the mouth result in very dramatic changes in sound level.

Directional Microphones

Use a directional microphone. Hypercardioid is better than cardioid, which is better than omnidirectional. All sound waves impinging on the microphone from a direction other than the intended signal is "noise" and will lower the threshold of feedback.

Effects

If you are using vocal effects like reverb, chorus or delay, turn them off until you can get sufficient gain before feedback to get performance level volume. Then add the effects back into the signal chain (one at a time) so you can be aware of the individual impacts that each effect is having on feedback.

Open Microphones

Use as few open microphones as possible. When a microphone is not in use, if possible, turn it off. If you have a T1 ToneMatch Audio Engine consider using the noise gate to do this automatically.

EQ and Tone Controls

Use the high-frequency tone control for the microphone channel carefully. Feedback could occur when this is set too high.

Instrument Pickups

Wherever possible, acoustic instruments should use pickups instead of microphones. Pickup systems provide much higher gain before feedback than microphones.

Using pickup can overcome the struggle to keep a consistent and close distance between the microphone and an instrument. Also, an instrument can be a source of feedback as it resonates with the amplified sound.

Distance Between Microphones

Another (low priority) design guide-line could be to keep open microphones as far apart as possible. Neighboring systems with open microphones can mutually decrease gain before feedback.

Techniques specific to the L1 family of products

- All players should be playing / singing through the L1 closest to them.

- If you are using a T1 ToneMatch Audio Engine it is often possible to use the parametric EQ section to notch the frequency that is causing feedback. You can find details in the article: Using the T1® to Control Microphone Feedback

- When stand mounting a directional microphone, tilt the microphone up ten or twenty degrees off the horizon so that it is less sensitive to direct sound from the speakers.

Does Microphone Sensitivity Affect Feedback?

It is a common misconception that a microphone that has lower sensitivity (in other words, a sound of a given intensity at the microphone produces a lower electrical signal than a microphone of higher sensitivity) is somehow more susceptible to microphone feedback.

In the argument that follows, the assumption is that other variables in comparing two microphones are equal. In other words, only the sensitivity differs.

Feedback occurs when the sound from the loudspeaker (or loudspeakers if a microphone is connected to more than one) is louder at the microphone than the sound of the voice.

If you just decrease the microphone sensitivity, the sound from the loudspeaker goes down by the amount of the sensitivity reduction.

If you restore the level from the speaker by adding more gain at any trim or volume control, the difference between the level of the speaker at the microphone and from the voice is restored.

When the added gain exactly compensates for the reduced microphone sensitivity we have the same difference as before. If the microphone fed back at a certain level in the room before, it will do so again at the same level in the room. This is obscured by the other variables that tend to change when we pick a microphone with a different sensitivity: different microphone frequency response and polar pattern details, different placement, etc.

The only way to get more gain before feedback is to lower the strength of the feedback path (the path between the speaker and microphone ) while the feed-forward path (the path from the voice to the microphone ) has the same gain. The microphone has to be in a quieter part of the sound system’s coverage or the microphone has to be directionally resistant to the speaker’s sound field compared to how well it picks up the desired input.

So it all comes down to one thing: when there is enough loudness in the room, how much better can the microphone hear the desired source than it hears the sound system? Sensitivity doesn't enter into this equation.

Other References

- Microphone Techniques for Live Sound Reinforcement Shure Educational Publication 2006 39 pages - pdf format